I just bought a used guitar, so I wanna talk about hands.

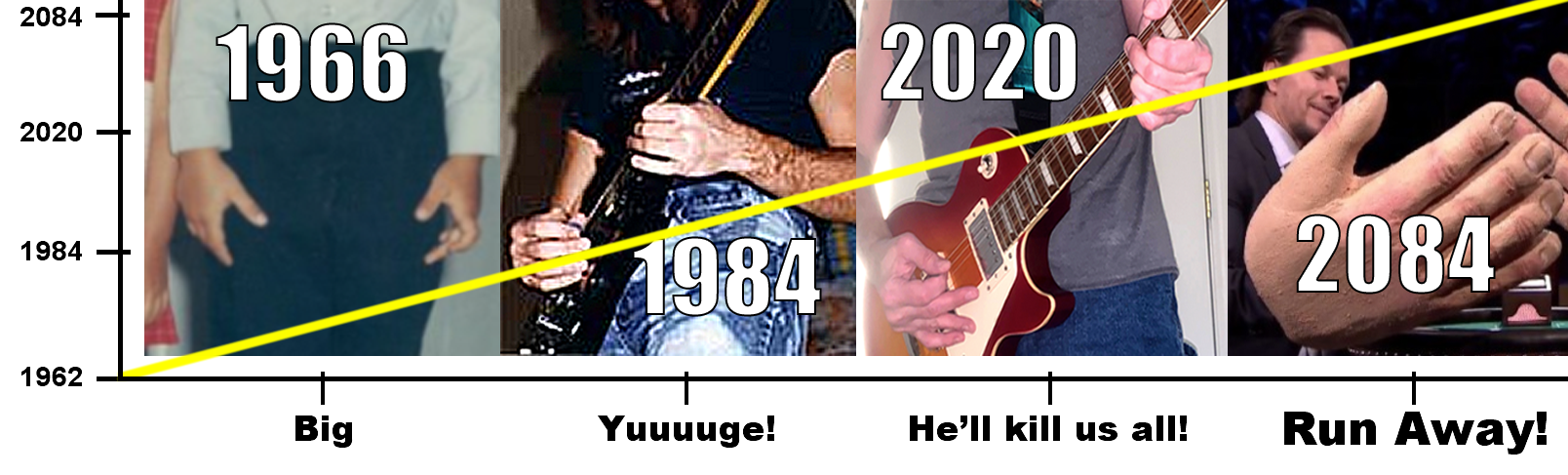

I’ve always had big hands. Today I look like an average-sized guy with big hands, but when I was a kid? Oh boy.

I have a picture of my sisters and me taken when I was 4 years old. I didn’t look like a kid with big hands; I looked like a kid wearing a pair of those giant foam hands they use to play Slapjack on The Tonight Show With Jimmy Fallon.

The used guitar I just bought is a Gibson Les Paul. I’ve always wanted one, but they’re hella expensive. Best Half spotted a guy on Craigslist selling a Les Paul, though—he was selling a lot of equipment, including the Les Paul, for which he wanted only $350.

A Les Paul these days can run $2,500 or more, especially if you get chrome PAF Humbucker covers, mother-of-pearl fingerboard inlays, the sunburst finish and some of the other goodies on the one I just bought.

I drove down to Cordes Junction to take a look at the guitar. The seller was a groovy older guy who looked like a cross between Gandalf and Jerry Garcia: gray and white shoulder-length hair, ZZ-Top beard, tie-dyed T‑shirt, the works. We could have been long-lost twins.

The Les Paul was in beautiful shape; almost mint condition. Gandarcia said he had a bad shoulder and the Les Paul was just too heavy, and he had arthritis so he couldn’t play as much as he used to anyway.

He didn’t care about getting his money back as much as he cared about finding a good home for the guitar. I liked him and I liked the Les Paul, so I bought it.

(He also had a 100-watt Marshall amp he wanted to place in a good home, but I like being married so I regretfully declined.)

Back in 1982, when I was 20, I saved up and bought a Gibson Invader, which was a budget Les Paul: It didn’t have the sculpted maple top, the mother-of-pearl fingerboard inlays, and other pricey options.

But it was still a damn fine guitar, and since it was less expensive it was like having a project car: I didn’t mind hot-rodding it up. I replaced the bridge pickup with a Seymour Duncan model I found at a pawn shop; drilled a hole between the knobs and added a phase switcher; yanked out the stock pots and installed butter-smooth CDS (or was it Alpha-Control? Don’t remember) pots with handmade caps so crystalline they could make a brave man weep, locking strap buttons—Eddie Van Halen may have coined the term FrankenStrat, but I think I could legitimately claim the name Mutant Invader.

My friend Rob, who has a habit of naming things I own, named the guitar Sledge. And I played Sledge, to use a tired old cliché, until my fingers bled.

Not long after I adopted Sledge, I moved in with my friend George. George is an amazing drummer, and our living room was jammed with both our stereos, my guitar and amp and other accoutrements, and George’s drum kit, which looked like the mother ship from Close Encounters of the Third Kind, except it was bigger and more expensive.

And we had a lot of friends who would come hang out: the aforementioned Rob, Tori, Dave, Daniel—who gave me an Electro-Harmonix Golden Throat talk box: DAMN Daniel!—Kim, John, and I’m sure there were others.

And they were all excellent musicians, and we would jam, which means they would jam, because I was still learning to play, so I stumbled around in the background on guitar, sounding like Linda McCartney sort of playing keyboards and kind of singing along with Paul, who was too kind to tell her the sound guy had her microphone turned off.

Harsh truth: I loved playing guitar, but I was caught in that frustrating trap of having juuuust enough talent to understand what really good guitarists were doing, but knowing I’d never ever be that good.

That was okay. I didn’t need to make a living playing guitar, and I was lucky enough to spend time with some really good musicians and enjoy bothering the neighbors with them.

Like most guitar guys I accumulated a lot of gear: stomp boxes, a real live tube amp from Fender that tried very sincerely to kill me, but that’s another story, and a pink paisley Telecaster that yes, looked just like the one Prince played, although I hadn’t heard of him yet.

I mutated the Telecaster even more; primarily with EMG active pickups that were encased in black ceramic blocks and looked unbearably cool, plus other stuff I won’t bore you with, before I finally admitted I just didn’t like the Telecaster.

Oh, it looked cool and it sounded good when I played it, but it sounded GREAT when any of my real musician friends played it. Also, Rob never named it anything, even though it looked like it was painted with Pepto Bismol. What was he supposed to name it–Dr. Pep and the Toe Biz Maulers? I’m sorry, but–wait; that’s actually an awesome name for a band, much less a guitar. But I think he knew it wasn’t going to work out for us and he didn’t want to make the breakup any more painful.

It was the neck. A lot of Fender guitars have one-piece rock maple necks, and the Telecaster was one of them. But it was too skinny, and with my freaky huge hands I felt like I was playing a pencil.

Our pastor’s son was 12 at the time. He’d saved up lawn-mowing money and bought a really beat-up, lifeless acoustic guitar. He was saving up to buy an electric guitar, and then he planned to save up even more and buy an amplifier.

So I gave him the Telecaster and said he could just worry about saving up for a new amp. I didn’t see any point in trying to recoup the money I’d spent fixing it up when I could give it a good home with someone who needed it and was already a far better guitarist than me.

And 30 years later, I found a beautiful Les Paul that needed a good home. Karma, baby.

I have exactly one photo of myself from the years I spent living with George and the musicians’ commune we operated: I think I was 22, and I’m playing Sledge. I was about as tall as I am now, but pipecleaner skinny, and my hands are still ridiculously big, if not as X‑Man mutant big as they were when I was a kid.

When 1995 rolled around, I’d been married for a while and No. 1 Son was on the way, so I did what any red-blooded American man would do: I quit my job, sold our house and moved us all to Oregon so I could go to college.

And while we were packing up to move, I made two bad decisions that still haunt me: I looked at the big pile of guitars and amps and stomp boxes and other gear I’d accumulated, and I decided it took up way too much room.

I also got rid of an antique barber chair for the same reason. That chair was ridiculously cool.

Sometimes you see these memes asking what you would say to yourself when you were a teenager; I would tell myself not to get rid of my guitar stuff and not to give away the barber chair. But I probably wouldn’t listen. I’m stupid that way.

So I loaded up the car with all my gear, except for a grungy old JDS acoustic I wanted to keep because I liked dragging it to concerts to see if I could get signatures on it, so Randy Stonehill, Phil Keaggy, Terry Talbot and Barry McGuire had all signed it.

(I also have a Village Inn kids’ coloring book/placemat that No. 1 Son and Barry McGuire colored together when No. 1 Son was 3, but that’s yet another story).

I drove to a music store in Topeka, the name of which I forget, but it was on 17th Street behind a no-kill cat shelter that used to be a Hardee’s, and I traded it all in on a really nice 12-string Washburn acoustic, which I still have but play only on the rare occasion when I want to play Supertramp’s “Give a Little Bit,” because the stupid-big fingers on my stupid-big hands make the guitar sound like a couple of cats running around fighting on top of it.

It didn’t take long to regret my decision. Three days later, as we hit Interstate 70 west on our way to Oregon, I exclaimed “Why the HELL did I get rid of 12 years’ worth of stuff I loved? Why didn’t I just get rid of the sofa or the TV or Best Half?”

Best Half, who was in the car with me, expressed her displeasure at this remark by giving me a pinch that still hurts today.

And so I went to college and met many other musicians who were better than I’ll ever be, including Andy Gurevich (the titular guru of the Gurevichian cult, which is also another story), Matt, John, and some more folks I hope I don’t offend by not remembering them.

And I watched them play and I enjoyed it, but I missed being able to stumble around uselessly behind them.

And I vowed that even though my playing sucked, someday I would buy another electric guitar, just as soon as I could afford to feed my family with something more than Top Ramen.

But that never happened, because I was too busy ruining my hands. Which reminds me of my dad’s funeral, which I’ll get to in a minute.

I had a series of stupidly dangerous jobs in my 20s and early 30s: I worked night shift in a convenience store, in a state hospital with the mentally ill, and as a rescue mission chaplain before college. No, not as dangerous as being a cop or a firefighter, but then again cops and firefighters have training and equipment and insurance and stuff.

During and after college I also worked as a concrete mason and on security teams in college and in church and elsewhere.

After that I got a job doing web development, which I loved, but which also helped me build up a lovely nascent case of carpal tunnel syndrome.

But after all the stupid dangerous jobs I’d had, I got bored with having a safe office job, so I joined a Kempo karate school to spend more time with my kids, and wound up liking it and helping teach (even though I was about as good at martial arts as I was at guitar). Which also did not do my hands any favors.

I have some really cool scars and stories about grievous injuries to my hands and forearms: A spectacular (human!) bite scar on the back of my right hand; a scar and nerve damage on my right wrist from being hit with a broken bottle; a fractured ring finger that healed crooked; a burn scar at the base of my thumb from being splashed with sulfuric acid (yet another story), several broken knuckles, assorted connective tissue injuries from breaking bricks at Kempo demos, and other stuff I forget.

That was just my right hand. I abused my left hand even worse:

During a Kempo sparring match I blocked a punch with my left pinky finger, which emitted a gloriously horrible snap that made everyone in the room wince; I caught my hand between an engine block and a garage floor; I got hit on the back of my forearm so hard a bunch of ganglion cysts showed up later; and I got mauled by dog who took a couple of good chomps out of my forearm and hand and left behind a big numb area.

Oh, and I also got diagnosed with MS, which causes some stiffness and numbness in my left arm and hand, and to top it all off I’ve got a bit of arthritis here and there in both hands that I’m sure will be loads more fun in the future.

(A couple months ago I saw an orthopedist to look at some arthritis in my left hand. They sent me an intake packet and wanted extensive, detailed info on any injuries I’d had to my hands. So I wrote down all that stuff you just read. The doctor came in, skimmed my stuff on the clipboard, and said, “What’s all this? Are you Jackie Chan’s bodyguard or what?” I told him I’m just clumsy.)

Just before Dad’s funeral two years ago, I… what? No, that’s not a non sequitur; I said I was going to talk about my dad’s funeral right up there. Pay attention!

Just before Dad’s funeral started, Mom and my sisters and my kids and Best Half and I all went up to view him in his casket, and to give him some gifts: I gave him a Johnny Cash CD; The Chowder gave him a little apple pie (another story), and others I can’t remember.

The funeral director was there, discussing Dad’s appearance with Mom, and he looked at Dad’s hands and remarked, “These are the hands of a man who worked hard.”

True. Dad was a glazier for more than 40 years; he also did handyman work on the side for those 40 years and also rebuilt or remodeled just about everything in our house to boot.

After he retired he did handyman stuff almost full-time (I remember him joking that retirement was boring, what with only 40–50 hours of work a week). He was in demand as the maintenance guy for a number of rental houses and small apartment buildings.

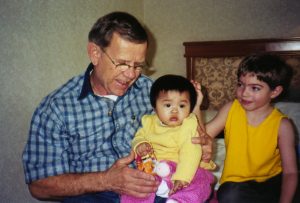

Today I was looking at a picture of Dad taken in April, 2002: He’s sitting on a hotel room bed next to No. 1 Son, who was 6 years old, and he’s holding The Chowder, who was 7 months old.

The hotel room bed was in Changsha, Hunan Province, in China. And the reason we were there was to adopt The Chowder.

Dad’s hands were smaller than mine (hell, Bigfoot’s hands are smaller than mine). But they were thick and callused and corded with muscle and scars, and they looked like two bags of walnuts.

Right now I’m 5 years younger than Dad was in that photo. And while I’ve never made a living working with my hands, other than the aforementioned stint as a concrete mason in college, I like to think I’ve inherited some of his better traits:

He had a beatup old poster in the glass shop he worked in; it said “If you don’t have time to do it right, when will you have time to do it over?”

He wasn’t preachy or pushy; all he did was set a standard and then demonstrate it.

I delivered the eulogy at his funeral; later some guys he’d worked with, plus his former boss, told me his co-workers would gripe at times that Dad was kind of slow and didn’t turn things around as fast as everyone else.

His former boss told me how they answered that gripe: “Yeah; he’s a bit slower. But he never, ever has to go back and redo anything.”

It’s only been for about the last 10 years of my life that I’ve realized just how much that influenced me, without him lecturing or preaching at me once.

I’ve owned a couple of houses; I’ve worked as a writer, a graphic designer, an editor, a web designer and a web developer. When I do stuff I try to find a way to do it elegantly and simply, to avoid quick-and-dirty solutions in favor of doing it right the first time.

The other day I was sitting on the floor in our living room and tuning the Les Paul. Pepper was lying in front of me with her head on my knee, gazing adoringly up at me like she was Rose DeWitt and I was Jack Dawson.

Best Half thought that was cute and took a picture with her phone.

When I saw the photo I chuckled at the way Pepper was making eyes at me, but then I noticed that my hands looked like sacks of walnuts, just like my dad’s hands.

Most of the jobs I’ve had in my life don’t create a tangible legacy; I can’t point at things I’ve made or fixed, or artwork or books I’ve written or things I’ve built.

But my hands look a lot like my dad’s hands; a coincidence of genetics and life experiences for sure, but I can live with having huge, half-ruined hands if it means I can honor my dad’s legacy a little bit.

Oh, my friend Rob named the Les Paul for me: Its name is now More Paul.